Essentially, forward and futures contracts are agreements that allow traders, investors and commodity producers to speculate on future asset prices. These contracts can act as a commitment between two parties to trade an instrument at a future date (expiration date) at a price agreed upon when the contract was created.

The underlying financial instrument of a forward or futures contract can be any asset, such as equity, commodities, currencies, interest payments or even bonds.

But unlike forward contracts, futures contracts are standardized contracts (as legal agreements) from a contract point of view, and are in a specific place (futures contract trading platform) Trading. Therefore, futures contracts are subject to a specific set of rules, which may include, for example, contract size and daily interest rates. In many cases, futures contracts are executed under the guarantee of a clearing house, which allows parties to trade with lower counterparty risk.

Although primitive forms of futures markets were formed in Europe in the 17th century, Dojima Rice Club (Japan) is believed to be the first futures exchange established. In early 18th-century Japan, most payments were made in rice, so futures contracts began to be used to hedge against the risk of unstable rice prices.

With the advent of electronic trading systems, futures contracts and a range of use cases have become common throughout the financial industry.

Functions of futures contracts

Futures contracts in the context of the financial industry usually have the following functions :

Hedging and Risk Management: Futures contracts can be used to mitigate certain risks. For example, farmers can sell futures contracts on their products to ensure that they will be able to sell their products at a certain price in the future, despite adverse events and market fluctuations. Alternatively, a Japanese investor holding U.S. Treasuries could purchase a yen-to-dollar futures contract equal to the amount of the quarterly coupon payment (interest rate), locking in the yen value of the coupon at a predetermined interest rate, thus hedging his U.S. dollar exposure.

Leverage: Futures contracts allow investors to establish leveraged positions. Because the contract settles on expiration, investors can use leverage to build positions. For example, a trader using 3:1 leverage can open a position up to three times his or her trading account balance.

Short Exposure: Futures contracts allow investors to gain short exposure to an asset. An investor decides to sell a futures contract without owning the underlying asset, a situation often referred to as a "naked position."

Asset Diversification: Investors gain exposure to assets that are difficult to spot trade. Delivery costs for commodities such as oil are often high and involve high storage fees, but by using futures contracts, investors and traders can speculate on a wider range of asset classes without having to physically trade them.

Price Discovery: The futures market is a one-stop shop for buyers and sellers (i.e. supply and demand) A gathering point of parties) that can trade multiple types of assets, such as commodities. For example, the price of oil may be determined by real-time demand in the futures market rather than local interactions at the gas station.

Settlement mechanism

Arrival of futures contracts The expiration date is the last day of trading activity for that particular contract. After the expiration date, trading stops and the contract is settled. There are two main settlement mechanisms for futures contracts:

Physical settlement:The two parties signing the contract Exchange the underlying asset at a predetermined price. The party going short (selling) is obligated to deliver the asset to the party going long (buying).

Cash Settlement: Does not trade the underlying asset directly. Rather, one party pays another party an amount that reflects the current value of the asset. An oil futures contract is a typical cash-settled futures contract, which exchanges cash rather than barrels of oil, because actually trading thousands of barrels of oil is quite complicated.

Cash-settled futures contracts are more convenient than physically settled contracts, even for liquid financial securities or fixed-income instruments where ownership can be transferred fairly quickly ( At least compared to physical assets such as barrels of oil), and therefore more popular.

However, cash-settled futures contracts may lead to manipulation of the price of the underlying asset. This type of market manipulation is often referred to as "close price manipulation," a term that describes unusual trading activity that intentionally disrupts the order book as a futures contract approaches its expiration date.

Exit strategy of futures contracts

After holding a futures contract position, futures traders mainly Three operations can be performed:

Closing: Refers to by creating a reverse transaction of the same value The act of closing a futures contract. So, if a trader is short 50 futures contracts, he can open a long position of the same size, offsetting his initial position. Offsetting strategies allow traders to make profits or incur losses until the settlement date.

Rollover: When a trader decides to open a new futures contract position after offsetting his initial contract position , an extension will occur, which is essentially an extension of the maturity date. For example, if a trader is long 30 futures contracts expiring in the first week of January, but wants to extend the position by 6 months, he can offset the initial position and open a new position of the same size, setting the expiration date for the first week of July.

Settlement: If the futures trader does not close or roll over the position, the contract will expire on the Settlement. At this point the relevant party is legally obligated to trade the asset (or cash) based on their position.

![]()

Futures contract Price patterns: contango and backwardation

From the moment a futures contract is created until settlement, the market price of the contract will continue to change with changes in buying and selling power.

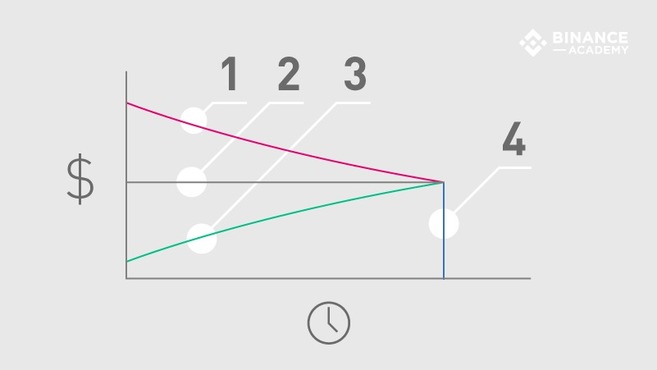

The relationship between a futures contract's expiration date and price changes creates different price patterns, often called contango (1) and backwardation (3). These price patterns are directly related to the asset's expected spot price (2) at maturity (4), as shown in the chart below.

Contango (1):A market condition in which futures contract prices are higher than expected future spot prices.

Expected spot price (2): The expected asset price at settlement (maturity date). Please note that the expected spot price is not always constant, i.e. the price may change as market supply and demand change.

Contango (3): Futures contract prices are lower than in the future Market conditions for expected spot prices.

Expiration date (4): A specific futures contract can be settled before settlement The last day of trading activity.

While contango market conditions tend to be more favorable for sellers (short positions) than for buyers (long positions), backwardation markets are generally more favorable for buyers favorable.

As the expiration date approaches, futures contract prices are expected to gradually converge to the spot price until the two end up being the same value. If the price of a futures contract does not coincide with the spot price on the expiration date, traders can take advantage of arbitrage opportunities to make a quick profit.

When contango occurs, futures contracts trade at a higher price than the expected spot price, usually for greater convenience. For example, futures traders may decide to pay a premium for a physical commodity that will be delivered at a future date so that they don't have to worry about paying costs such as storage fees and insurance premiums (gold is a classic example). Additionally, companies can lock in their future spending at a predictable value through futures contracts, purchasing commodities that are integral to providing their services (such as a bread producer purchasing wheat futures contracts).

On the other hand, a backwardation market occurs when futures contracts trade at a price lower than the expected spot price. Speculators who buy futures contracts hope to profit if prices rise as expected. For example, if the expected spot price for a barrel of oil next year is $45, a futures trader might buy a barrel of oil contract today for $30 a barrel.

Summary

As a standardized forward contract, futures contracts are the most common in the financial industry. One of the most commonly used tools, its features are versatile and suitable for a wide range of use cases. But before investing money, be sure to learn more about the basic mechanics of futures contracts and their specific markets.

While "locking in" future asset prices can be useful in some situations, it is not always safe, especially when trading contracts on margin. Therefore, risk management strategies are often required to mitigate the inevitable risks associated with trading futures contracts. Some speculators also use technical analysis indicators as well as fundamental analysis methods to understand price behavior in the futures market.

Forum

Forum Finance

Finance

Specials

Specials

On-chain Eco

On-chain Eco

Entry

Entry

Podcasts

Podcasts

Activities

Activities

OPRR

OPRR